Missouri voters rejected a right-to-work law through a ballot referendum this week. The measure, known as Proposition A, would have made it illegal for unions to charge fees to workers they represent who choose not to pay them. Labor advocates argue that voter rejection of the initiative by margins of more than two to one suggested a revival of the power of labor unions, particularly in light of a recent Supreme Court ruling against public-sector unions.

Missouri voters rejected a right-to-work law through a ballot referendum this week. The measure, known as Proposition A, would have made it illegal for unions to charge fees to workers they represent who choose not to pay them. Labor advocates argue that voter rejection of the initiative by margins of more than two to one suggested a revival of the power of labor unions, particularly in light of a recent Supreme Court ruling against public-sector unions.

Proposition A Defeated at Polls

In states without right-to-work laws in place, employees at unionized workplaces who are not members of the union have to pay “fair-share” or “agency” fees. These fees, which are lower than the dues union members pay, cover the costs associated with collective bargaining.

Right-to-work laws make it illegal for a union to charge these fees. Union finances can be strained under such laws because they give workers an incentive not to pay union dues – known as the “free rider” problem, in which workers benefit from union contracts but choose not to pay for them.

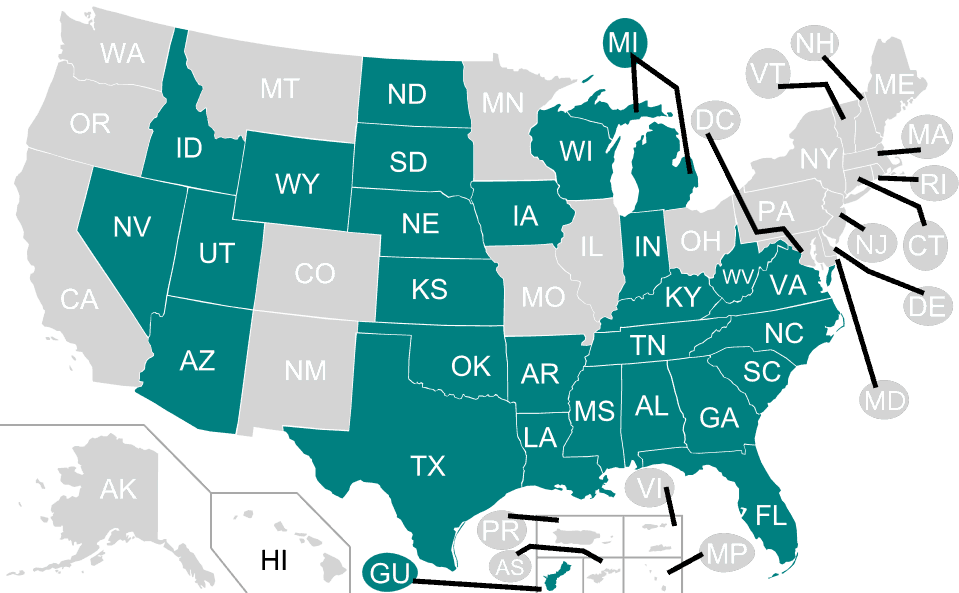

Missouri was poised to become the 28th state to enact a right-to-work law last year, when the state’s then-governor, Republican Eric Greitens, signed Senate Bill No. 19 on February 6, 2017. The law would have prohibited labor unions from collecting dues as a condition of employment. Greitens and the legislators who passed the bill argued that the change would lure businesses to Missouri and make the state competitive with other states that have similar laws. State Democrats had opposed a right-to-work law as a ploy to weaken labor, with the previous governor, Democrat Jay Nixon, vetoing a similar measure.

The passage of the Missouri right-to-work bill prompted workers and unions leaders to organize a massive campaign to defeat the law. They gathered 300,000 signatures – more than double the number needed – to freeze the law and put it on the ballot for voters to decide.

A union-backed campaign raised $15 million to urge voters to reject the measure, known as Proposition A, in Tuesday’s election, an amount that was more than five times the money raised by two business groups supporting the right-to-work bill. According to the AFL-CIO, union members knocked on approximately half a million doors to mobilize voters to the polls. The campaign also recruited actor John Goodman, a Missouri native, to record a radio ad against the measure, in which he said “The bill will not give you the right to work. It’s being sold as a way to help Missouri workers, but look a little deeper and you’ll see it’s all about corporate greed.”

The campaign’s efforts proved to be effective, with 67.5% of voters rejecting Proposition A. The election marked the first time voters have overturned a right-to-work law via a ballot referendum since Ohio attempted a similar measure in 2011.

Right-to-Work Laws Benefit Business Owners, Not Workers

Since Republicans took over a historic number of state legislatures in the 2010 midterm elections, lawmakers began to expand right-to-work laws from the South to Midwestern states with strong union presences. In 2012, Indiana and Michigan passed right-to-work laws, with Wisconsin, Kentucky, and West Virginia later following suit.

A similar blow was dealt to public-sector unions across the country on June 27 of this year, when the United States Supreme Court ruled 5-4 in favor of the plaintiff in Janus v. American Federation State, County, and Municipal Employees, Council 31 (also known as Janus v. AFSCME), arguing that the application of public-sector union fees to non-members was a violation of First Amendment rights.

Politicians and pro-business groups who advocate for right-to-work laws claim that they attract business and boost the economy. Economists, however, have found little evidence supporting these claims. A 2007 study conducted at Hofstra University demonstrated that right-to-work laws led to an increase in the number of businesses, but that the economic gains mostly went to business owners, while average wages for workers went down.

Similarly, the Economic Policy Institute, a progressive think tank, attributes a 3.1 percent decline in wages for union and nonunion workers alike because of right-to-work laws, after accounting for differences in demographics, cost of living, and labor market characteristics. In a 2014 study, economists at the University of Missouri Kansas City concluding that Missouri shifting to a right-to-work state would result in an annual loss of $1,945.00 to $2,547.00 per household.

Labor advocates hope that the failure of Proposition A represents a rising backlash against Republican right-to-work laws that harm unions. They also point to teachers in states like Arizona, Oklahoma, and West Virginia who in the past year have forced state lawmakers to raise business taxes to pay better wages, all with the support of their unions.

<< BACK TO BLOG POSTS